The earliest memories that I have of Aunty Pat are in the Mercedes college convent kitchen, she’s wearing her nun’s habit and we were getting the grand tour of the wonderful old place. I felt proud to have this privilege

Years later I remember camping out past Port Augusta, way out in the middle of nowhere and there we visited aunty Pat where she lived and ran little school for aboriginal people.

Later still I remember mum getting letters from exotic places which contained photos of Aunty Pat sitting among the palm trees, or perched upon the steps of some foreign looking building, with hand-written letters attached about the good work she was doing there.

God’s work.

After 20 years of being a nun she left the convent and that’s when we started seeing alot more of Aunty Pat.

She moved into a tiny flat by the beach. She loved the beach. I remember a tiny little kitchen at least 1 flight of stairs up, spotlessly clean with white walls, a suspended cupboard with glass sliding doors that was filled with familiar things, and Aunty Pat in blue jeans.

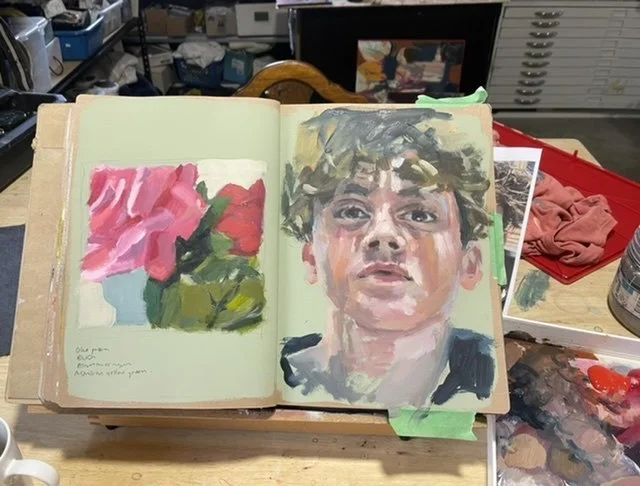

Years later, sometime in the early 2000s, Aunty Pat started writing her memoirs. She talked about it for a long time before she actually wrote it. I remember her talking about writing her memoirs when she took up art classes at Tafe, here we pondered the processes of her drawing and printmaking efforts as her portfolio grew and was looking pretty good, and we would chat about creative projects that could be turned into business endeavours that she would start, and maybe we could work on together after she’d written her memoirs.

She talked about writing her memoirs when she learnt the fine art of holistic massage, and set up a little remedial massage business in her spare room.

She was talking about it when she put her car on the ferry to Tasmania (she had a fear of flying), she stayed there for ages, so long that Mum took Nanna on a plane to visit her over there.

And she was talking about writing her memoirs when she decided to travel around the world by boat. I still can’t believe she did that. Maybe it was on that shipping container where she rented a tiny cabin for the journey back that she actually had some spare time to write her memoirs.

However she managed it it was not long after that journey that she threw a party, and out of the large box that was plonked on the floor of the her cozy Glengowrie kitchen, presented us all with a green novel sized book that had a photo of her hugging a tree on the front cover and the words - “you never know what comes to you.”- finally her memoirs were finished and published and we all got a copy with some to spare.

So now I will tell you a little bit of it in Aunty Pats own words as she saw it and wrote it in her memoirs.

(note: below I’ve taken excerpts from her memoirs and stitched them together to tell a little bit of her story in her own words.)

-

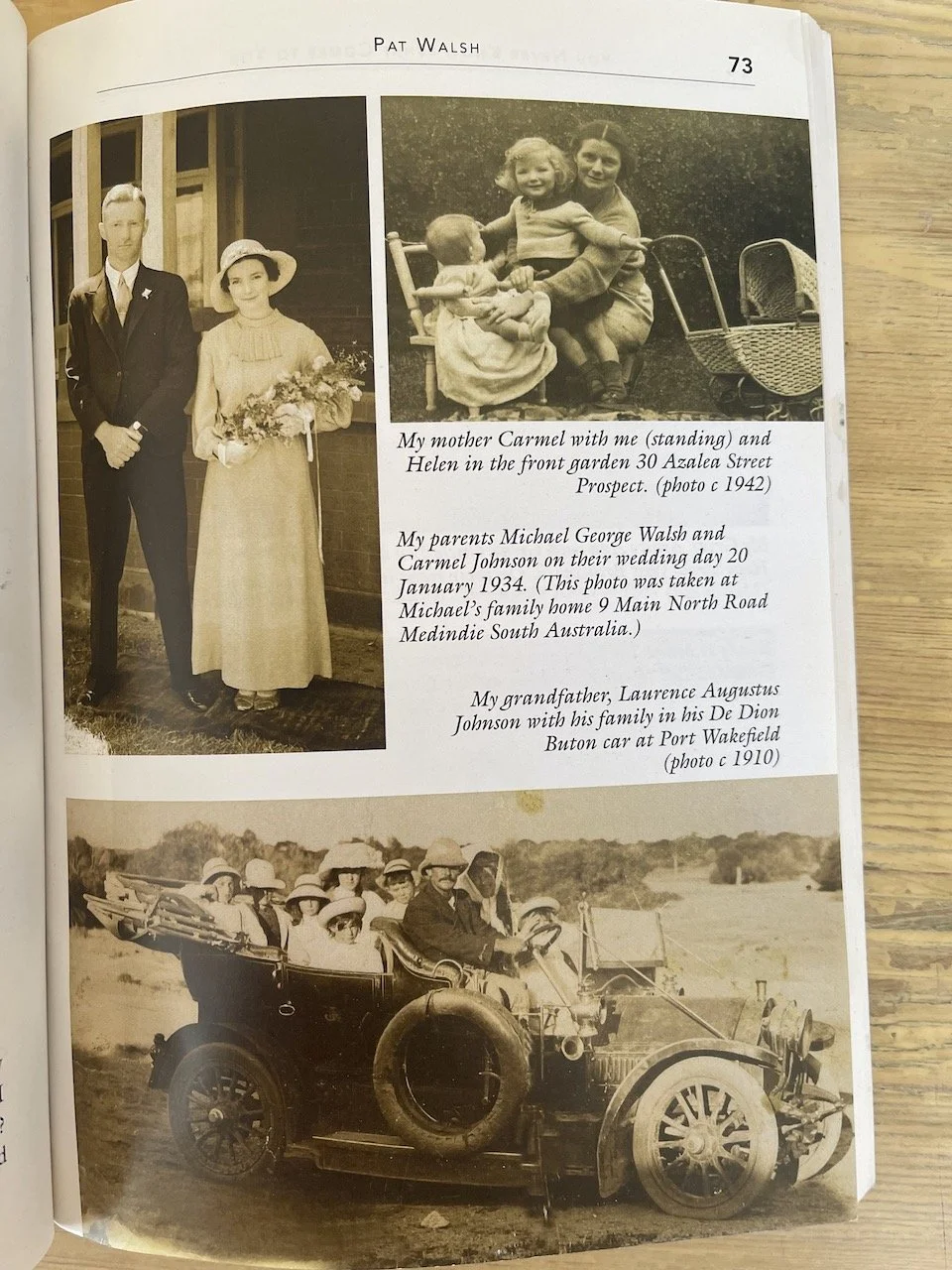

1939 - My arrival was somewhat mysterious. I came behind a thin membrane, a veil - a caul was covering my face. Cauls are said to be great good luck, a lifeguard against tempests and torrents They claim those born with a caul will never drown. And I haven’t.

That caul was to be the forerunner of other veils and enclosures to follow in my life.

-

My best birthday present arrived the day mum wheeled a ladies two wheeler bike down our passage - my ticket to freedom had landed and I was off too see the country - Gepps cross! Here the plains began and I saw funny half-tank like shaped buildings sprouting up. Dad told me these were the homes for new Australians.

-

It was the early 1950s when dad built our red brick beach house - perched on a hill in second avenue Moana. Mum proudly named it St Michael’s.

On the back of our large Moana block dad made a tennis court that gave us lots of room to play. More important than this play area was an even bigger play area that was walking distance from our house - Moana Beach.

Looking back today I cherish the opportunities we had at Moana to roam freely in natures art galleries. Our parents trusted we’d be safe, put a few restraints on us and off we’d go each morning. Our first port of call was Moana Kiosk, (still standing today). Here two shillings bought us two hours of riding the waves on a rubber surf shooter.

-

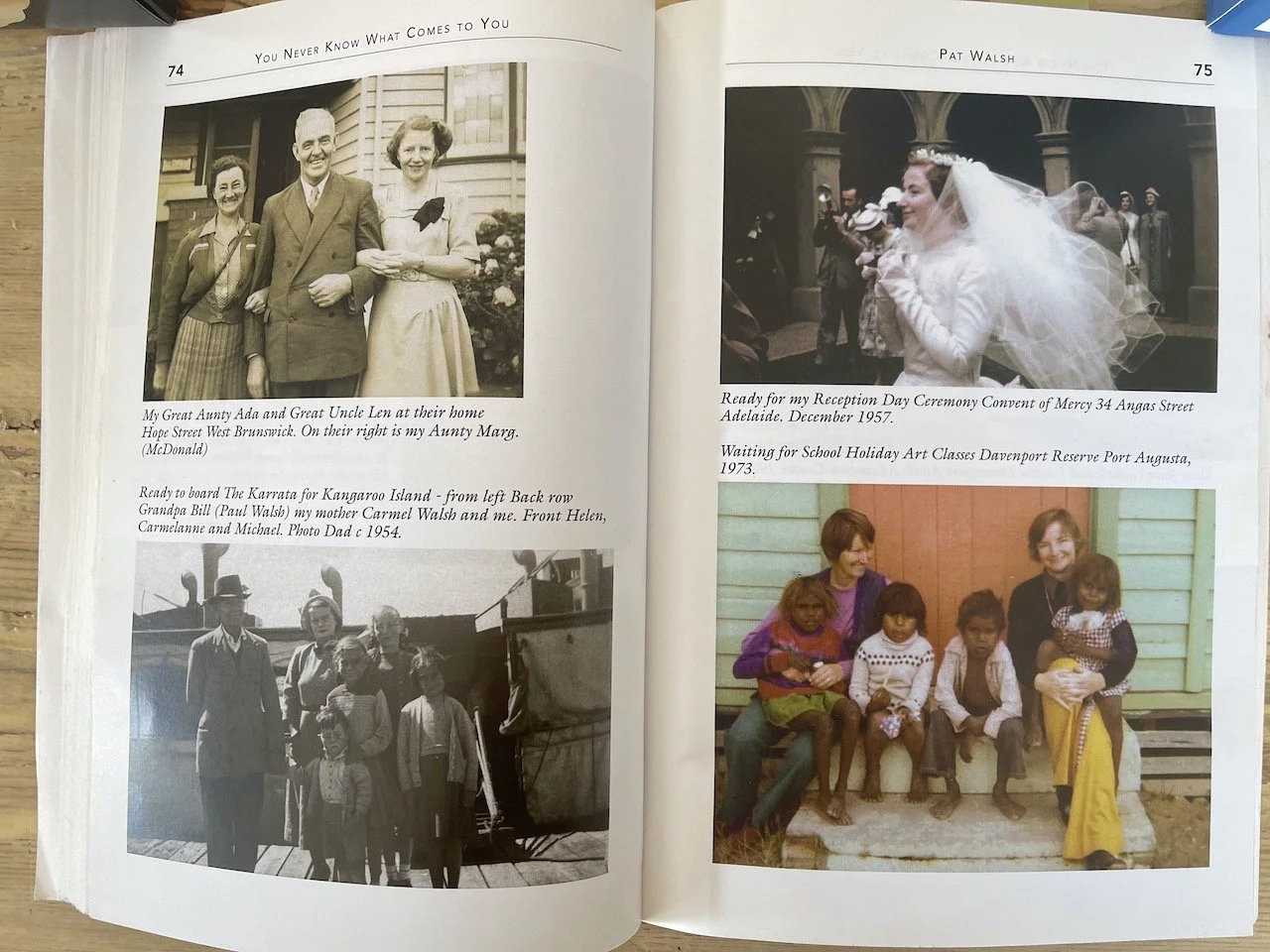

Back home on Azalea street Prospect, life reverted to our predictable meat and 2 veg routine.

Roasts on Sundays,

sausages and mashed potatoes on Monday

Crumbed Chops on Tuesday

Tripe with parsley sauce or lambs fry with bacon on Wednesday

Stew or steak and kidney pie on Thursday

Friday was fish and chips or that glaring orange English filet.

Saturday was a make-do day with soup and pasties when the footie was on, and cold camp pie, cooked corn beef, brawn or fritz and salads when the cricket was on.

-

Going to the walls…

Today I look back. Entering convent life was like I’d divorced my family and life beyond the convent walls. I didn’t have access to a phone, visiting days was once a month and it was as though I was now living in an overseas community.

In spite of this separation I enjoyed the novelty of my new life.

The novice mistress outlines the daily routine:

“The bell to rise will be at 5:25am and you are to be in the chapel at 5:50am for chanting (in latin).

After this there will be 30 minutes of meditation.

A short break then it was back to our stalls for mass in Latin at 7am.

Mass over in silence we filed to breakfast down a narrow corridor connecting the chapel and cloister to the former Barr Smith house.

Breakfast was taken in silence except on first class days, these were Holy days of obligation, like Christmas and Easter Sunday.

On second class days speaking was permitted from midday. On other days lunch was taken in silence.

Silence was a big part of convent life.

-

It’s now 1972 and I’m back with the trees at Mercedes college, assigned to teach grade four.

I’d already learned about teaching through teaching music for 10 years and now I was to learn about learning.

This Transformative experience was due to a wonderful teacher named Joan McKie.

Joan arrived with firm beliefs about learning and created a stimulating environment where children were free to learn. Under her inspiration the lower primary school was named Murakunji - an aboriginal word said to mean “many little whirlwinds often seen in large numbers”.

Under her creative plan children chose their own area of learning - sometimes they spent all morning, or all day or all week doing their chosen area of learning.

This child directed learning, with support from teachers, astounded me. All around I saw children productive and creative. They were self motivated, engrossed and stimulated with what they were doing.

-

I was doing aboriginal studies as part of my Batchelor of education, and one day finishing an assignment an idea of working with aboriginal children surfaced.

A few weeks later I was summoned to the principal’s office for a long distance call.

Lifting the receiver a deep voice boomed.

“Harold here. Would you be prepared to do a creative activities program with Aboriginal students at Davenport reserve in January?”

I’d heard Port Augusta was a pretty rough place and I wondered what an aboriginal reserve would be like.

-

Our accommodation on our first visit was in one of the white staff houses run by the department of community welfare. This staff house was a refuge after the draining heat when doing art with a bunch of enthusiastic aboriginal children. These kids were not fazed by the heat and came around peering through our window at 7:30am ready for more art.

-

later in 1974 - my superiors decided to fund two positions at Davenport.

This time Sr Joan and I were to pioneer a new course for adults on Davenport reserve commencing 1975.

I was 35 and full-time work with aboriginal people had called and found me.

Our classroom to be was bare and without air-conditioning. Our flat had an air conditioner however, and a lounge/kitchen area, bathroom, laundry and one bedroom. Joan and I shared the bedroom. This sleeping arrangement was a hurdle for me as since entering the convent eighteen years earlier I’d always had a cell to myself. This I now realised had been a luxury and now I needed a large chunk of adapting.

Suddenly I was confronted by an aboriginal woman:

“are you government?”

“no” I replied

“are you welfare”

“no” I repeated

she then shouted:

“I WANT A DIVORCE!”

Laughing I bleated out “I’m a teacher.”

Thinking back to those early days at Davernport I’m reminded of a day when I was sitting in the middle of the back seat of a car full of Aboriginal students. For some unknown reason, while we drove along I suddenly blurted out “I’m the only white fella here.”

This resulted in a laughing woman student who was besides me, patting me on the arm saying, “Don’t worry Bub - you’re black on the inside.”

My time at Davenport Pt Augusta was a high point in my life.

It was a time when barriers began to be pulled down and pushed away.

A time when the thoughts, ideas and energies of many people came together to create a unique Aboriginal community development program that showed new things were possible. It was a pivotal time in my life.

-

Today it’s ten years since my leukaemia scare and I’m well.

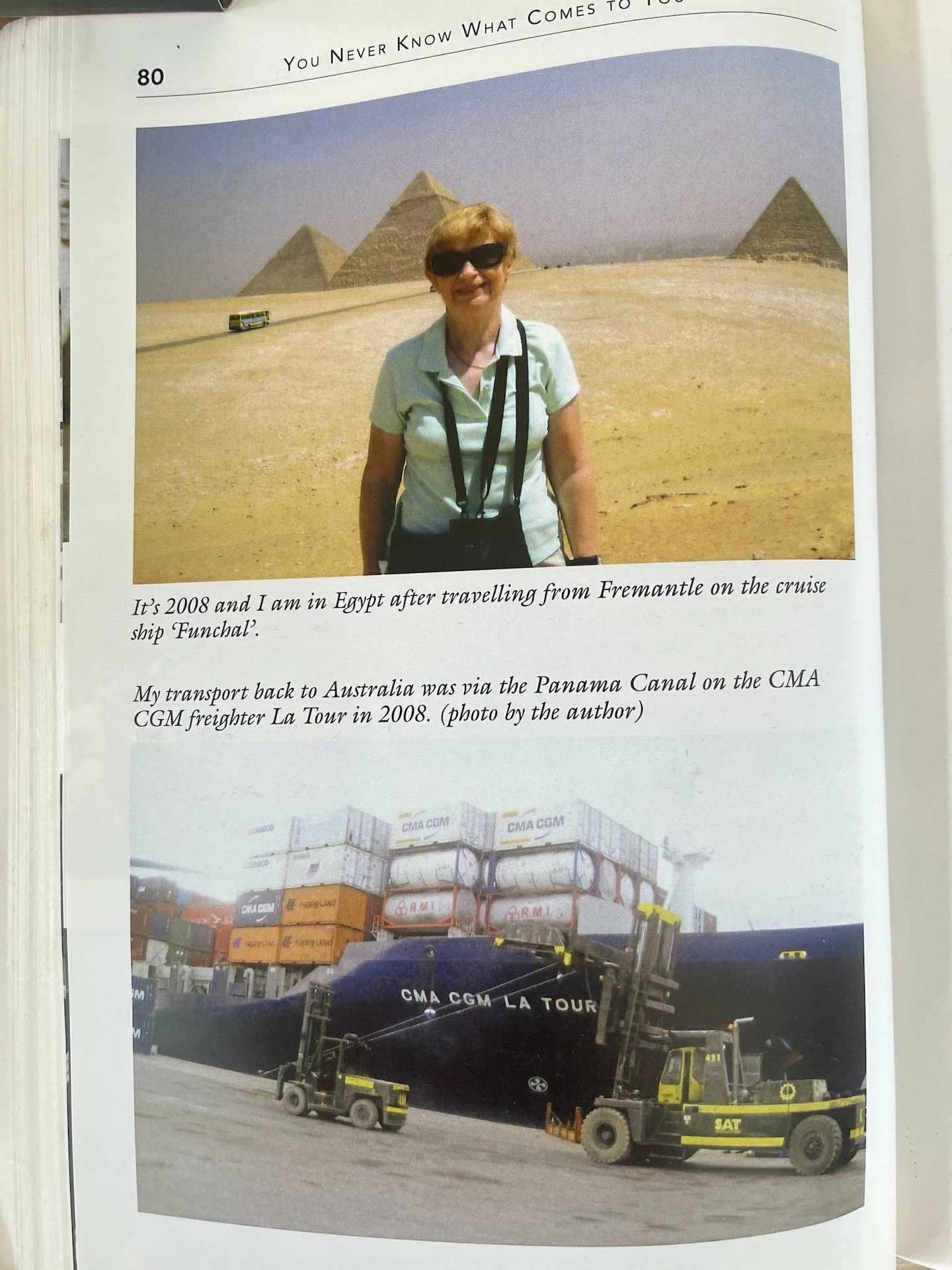

My time of chapels, churches and classrooms has long gone. Most days now I walk along Glenelg beach close to the sea’s edge as I admire nature’s wonders of the sea, sky and sand and man’s inventions as I see planes come and go from Adelaide Airport. I haven’t been on a flight for a couple of years - but what I have done is fulfil a dream to go around the world without one flight!!

…

Yes Aunty Pat did that in 2008, visiting every continent on the way - according to her it was quite an adventure she took a cruise ship from Fremantle through the Suez Canal to Europe - a bus tour of Spain, Portugal and Morocco. And even got a police escort at the port of Dunkirk to board a freighter bound for Australia via the panama canal.

…I can’t believe she did that, and what’s even more astounding is that she did it all by herself.

I’ll finish now with the quote found at the start of her memoirs by Margaret Mead. I love this quote and I believe Aunty Pat aspired to be the person this is about:

“If one doesn’t love one part of the earth and every tree and blade of grass on it, how are you going to love the whole world?

You know the planet isn’t very loveable all by itself.

But if you work up from your neighbourhood and the hills and the trees that you love and your own children and your own religious beliefs and you own language, you can end up loving the whole world.”